- Norwich Blogs

- Blogs

- What is a well-informed citizenry today?

What is a well-informed citizenry today?

The article argues that the Founders believed a well-informed citizenry is essential to self-government, but today’s information environment makes that harder than ever. It explains that being “well-informed” isn’t just about consuming a lot of information—it requires balancing volume with variety, because overload plus confirmation bias can leave citizens simultaneously overexposed and underprepared to think critically, making individual effort and responsibility more important than ever.

Disclaimer: These opinion pieces represent the authors’ personal views and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Norwich University or PAWC.

The rights and responsibilities of the citizenry

In 1789, Thomas Jefferson was serving as the U.S. Minister to France on the eve of the French Revolution. In a letter to his friend Richard Price, he wrote, “…wherever the people are well informed they can be trusted with their own government; that whenever things get so far wrong as to attract their notice, they may be relied on to set them to rights.”i While that particular quote was in a private letter that would not become well-known for many years, it succinctly describes an idea that permeated the nation from its founding.

A year earlier, our Founding Fathers were acting on what Jefferson eventually articulated. James Monroe, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay wrote a series of essays known as The Federalist Papersii under the pseudonym Publius to present their argument to voters in support of the Constitution. Several anti-federalists, like ‘Brutus’ (believed to be Robert Yates) and Patrick Henry, engaged in the public debate with the Anti-Federalist Papers.iii These essays and speeches provided enough information to the citizenry to play a crucial role in the formation of the United States of America. In the end, the Constitution was ratified, and a Bill of Rights was added, addressing many of the anti-federalists’ concerns.

It seems evident that a well-informed citizenry was considered essential to retaining the rights so hard-won during the Revolutionary War. The very public debate in the Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers was a concerted effort by political activists to ensure that the citizenry was well informed in 1788.

Too little or too much information

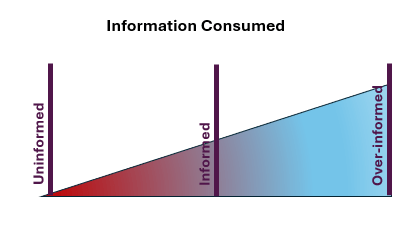

Let’s consider information on a linear scale:

The danger of too little information is evident in the context of a voting citizenry. To elect effective representation, the people need at least enough information to assess a candidate’s stance on the topics that most affect them. On the linear scale above, having too little information or being uninformed prevents individuals from being trusted agents in any type of democracy. At the opposite end of the scale, too much information is also a danger. Assuming the above scale is only addressing information consumed by the general population (not those in positions where information is required for success or advantage), too much information can cause harm in a practical sense such as in the case of Operational Security in military operations, but also philosophically can lead to a sort of Gnosiophobiaiv, or fear of knowing, fear of being obligated to act or hopelessness because of an inability to act. So, in the linear sense, too little information is uninformed, enough information is informed, and too much information is over-informed.

Too little AND too much information

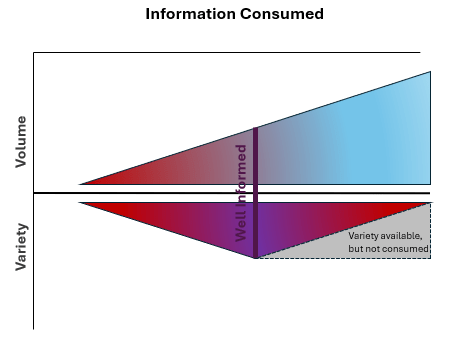

But that doesn’t answer the question of what makes a citizenry well-informed. I argue it is not as linear as it seems. While too little or too much information is problematic, too little AND too much could be just as detrimental to public involvement in policy creation. You become informed, but perhaps not well-informed.

And this is because the information consumed has two y-axis components for a well-informed citizen: volume and variety.

Having both too much and too little information, in other words, volume without variety, prevents critical thinking and causes our brains to revert to heuristics (mental shortcuts we use to speed up problem solving). There is more information available than most individuals can consume. To make sense of it all, our brains tend to choose the path of least resistance, meaning the information that most agrees with our current thinking is the most readily consumed, which then leads to a lack of variety…too much AND too little. If we could formulate it as a mathematical equation in which the amount of information consumed has a limit, the increase in volume would be equal to the decrease in variety.

Part of the issue is that our sources of information have increased a thousand-fold, which allows us to engage in confirmation bias by only absorbing sources that feed into our own bias, not for any nefarious reasons, but simply because the volume is more than we have the time or capacity to consume. Therefore, we choose the information that best reflects our own views. In neurological circles, this is referred to as motivated attentionv, which suggests that our brains have adapted to the volume of information available by subconsciously focusing on opportunities and threats, as these are the pieces of information most important to our well-being. This shortcut that our brains have developed makes it difficult to focus on reasonable (not a threat) but opposing (not an opportunity) viewpoints without a concerted effort on the part of the individual.

The amount of information we can process has increased by approximately 5% per year, according to some studies, based on human ability to adapt.vi However, the amount of information available increases exponentially due to the phenomenon of accelerating returns, or Moore’s Law, which conjectures that the processing speed of technology doubles every two years, based on the number of transistors that can be placed in an integrated circuit.vii With a variety of U.S. news outlets and access to global news and social media, there is nearly unlimited information. Since it doesn’t have to be accurate or relevant in the social media realm, the amount of information available is limited only by the human imagination and how quickly the internet can pull it up. However, the amount of information that an individual can effectively process is limited. Thus, every individual ends their day having absorbed volumes of information, but perhaps not a diverse enough variety to be considered well-informed, as envisioned by our Founding Fathers. Some of this is self-imposed, since we can certainly tune into a different news station or follow other people on our social media feeds. Some of it, however, is unavoidable because of how our brains handle the volume of information we receive.

Individual responsibility as a necessary part of our democracy

This leads back to the quote from Jefferson. We are entrusted to ‘set things right’ by voting for government representatives who will enact our will, but we can only do that by being well-informed.

In 1788, the volume of information was limited to a dozen or so pundits on two fairly distinct sides of a singular fence. The information space today is far murkier. On the surface, it may still seem as if there are two distinct sides. However, by incorporating far-left and far-right ideologies on both sides, along with additional noise from global sources, the bifurcated nature of politics becomes less clear. And rather than a few articulate political advocates shaping the arguments on our many-sided fence, as was the case in 1788, anyone with a social media account (articulate or not) contributes to both the volume and variety of information available.

Fortunately, we live in a country where every citizen not only has the right but is charged with the responsibility of self-governance by the founders of our nation. And they gave us the means to do so through an elected representative government. However, it is an individual responsibility to be well-informed so as to be a citizen who can be trusted with their own government.

Being well-informed means consuming information in equal measures of volume and variety. That takes work. No one can do that part for us.

The United States version of democracy is supposed to be a little messy. It was always meant to engender debate and tension. And it was always meant to have a well-informed citizenry available to hold it accountable. However, in today’s information space, individual citizens face a challenging task. The sheer volume of both information and misinformation makes being well-informed difficult and often exhausting.

However, it will always be worth the effort.

Retired Brigadier General Tracey Poirier most recently served as the Director of the Joint Staff for the Vermont National Guard until her retirement from service in October 2025. She graduated from Norwich University in 1996 with a bachelor’s degree in English and communications and is the only Norwich graduate to be selected as a Rhodes Scholar. After earning two master’s degrees from Oxford University in England, one in anthropology and one in human resource management, she went on to serve on active duty with the Marine Corps until 2004. In 2006, she re-entered military service with the Vermont National Guard, eventually becoming the first woman to be promoted to a flag officer rank in the Vermont Army National Guard. Additionally, she served as an administrator for Norwich University, culminating as the Assistant Vice President for Student Affairs, and continues to serve as an adjunct professor of anthropology.

i https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-14-02-0196 ii Hamilton, A., Madison, J., Rossiter, C., Jay, J., & Kesler, C. R. (2005). The federalist papers. Signet Classics, an imprint of New American Library, a division of Penguin Group (USA). iii Ketcham, R. (2003). The Anti-Federalist papers ; and, the constitutional convention debates. Signet Classic. iv Maslow, A. H. (1963). The Need to know and the Fear of Knowing. The Journal of General Psychology, 68(1), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1963.9920516 v Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., and Cuthbert, B. N. 1997. Motivated attention: affect, activation, and action. In: Lang, P. J., Simons, R. F., and Balaban, M. T., editors. Attention and Orienting: Sensory and Motivational Processes. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. p. 97–135. vi Bohn, R., and Short, J. 2012. Measuring consumer information. Int. J. Comm. 6:980–1000. vii Intel Newsroom Press Kit: Moore’s Law, Sep 2023, https://newsroom.intel.com/press-kit/moores-law#:~:text=Moore’s%20Law%20is%20the%20observation,must%20innovate%20in%20other%20ways