- Norwich Blogs

- Blogs

- Russia’s Long Game: Maritime Dominance, Territorial Consolidation, and the Coming Test in Moldova

Russia’s Long Game: Maritime Dominance, Territorial Consolidation, and the Coming Test in Moldova

By Dr. James M. Deitch

The article argues that Russia’s war against Ukraine is a coherent, long-term strategy focused on territorial consolidation, maritime dominance, and economic strangulation — aimed ultimately at landlocking Ukraine by seizing or neutralizing its Black Sea access. It warns that Western political fragmentation and mixed signals, alongside Russia’s likely use of Moldova as a low-risk testing ground, could enable a decisive spring offensive that reshapes Eastern Europe’s security balance and tests NATO’s resolve.

Disclaimer: These opinion pieces represent the authors’ personal views and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Norwich University or PAWC.

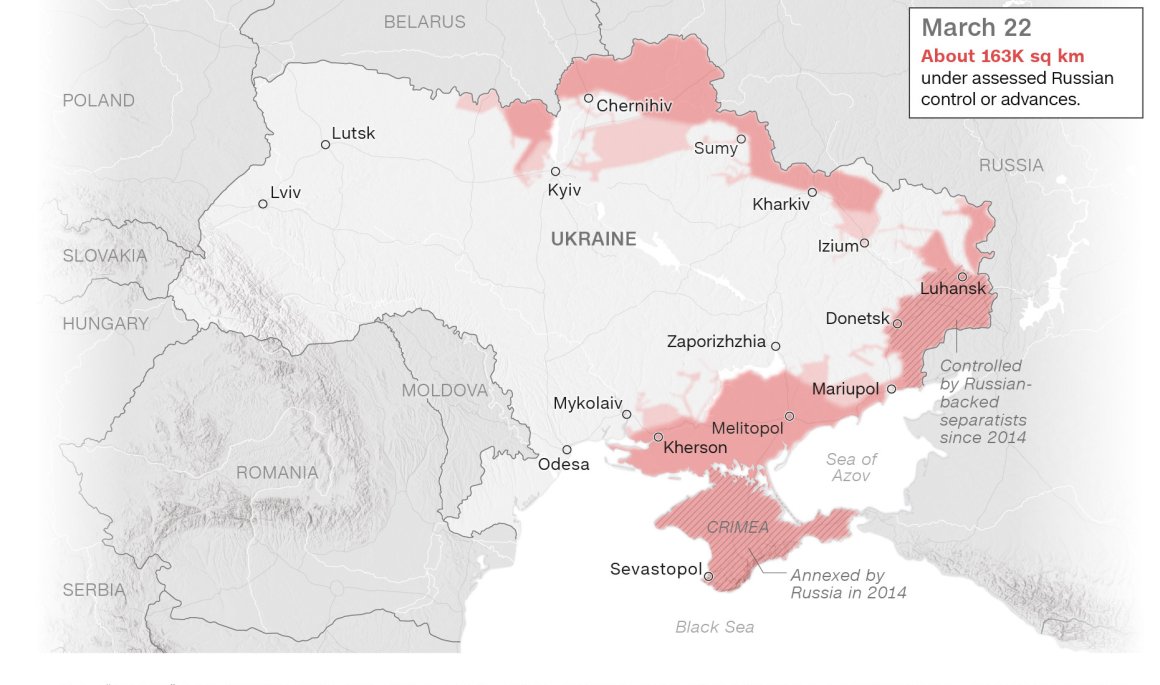

The war in Ukraine is often framed as a sequence of crises — Crimea in 2014, the Donbas conflict, the full‑scale invasion of 2022, and the grinding attrition that has followed. Yet this episodic framing obscures the deeper continuity of Russian strategy. In my assessment, Russia’s performance throughout the conflict points to a long war strategy built on territorial consolidation, maritime encirclement, and the systematic weakening of Ukraine’s economic and political capacity. As the conflict enters another winter and Western political cycles shift, Russia is positioning itself for a decisive spring campaign to close Ukraine’s remaining access to the Black Sea, destabilize Moldova, and test Europe’s willingness to defend its eastern frontier.

A Fractured West and Moscow’s Calculus

The diplomatic landscape has grown more volatile with the introduction of President Donald Trump’s 28‑point peace plan — a proposal that has intensified political anxiety in Kyiv, Moscow, and across Europe. As reported by multiple outlets, the plan would require Ukraine to surrender significant territory, including formal recognition of Crimea, Luhansk, and Donetsk as Russian territory, while freezing the front lines in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia.[1] It would also compel Ukraine to renounce future NATO membership, reduce its armed forces, and accept the withdrawal of all NATO personnel from its territory. Sanctions on Russia would be lifted, and frozen Russian assets would be redirected toward reconstruction. For Ukraine, these terms amount to coerced capitulation. President Volodymyr Zelensky has repeatedly stated that he has “no legal right” and “no moral right” to cede sovereign territory, rejecting the plan’s core concessions outright. European leaders have likewise warned that pressuring Ukraine into territorial concessions risks emboldening Moscow and fracturing Western unity. Rather than stabilizing the conflict, the plan has exposed the fragility of Western cohesion at the very moment Russia is preparing for renewed offensive action.

Compounding this instability is the uneven signaling from the United States and its allies. Washington’s rhetoric has swung between firm declarations of support for Ukraine’s territorial integrity and periodic suggestions that Kyiv may need to consider “difficult compromises.” Delays in military aid, congressional infighting, and fluctuating public statements have created the impression of a West committed in principle but hesitant in practice. Moscow has taken careful note. Russia has long believed that Western unity is brittle and that time, political fatigue, and domestic pressures will erode the coalition supporting Ukraine.[2]

Europe’s posture has been similarly fragmented. Eastern European states, acutely aware of the Russian threat, have pushed for sustained military assistance and a clear commitment to a Ukrainian victory. Western European states have often favored diplomatic engagement and gradual de‑escalation. Germany’s vacillation over weapons deliveries, France’s shifting rhetoric on negotiations, and Hungary’s persistent obstruction within the EU have reinforced the perception of a continent divided not only by geography but also by strategic worldview. Even when Europe presents a unified front on paper, the underlying fractures are visible, and Russia has calibrated its strategy accordingly. These inconsistencies matter because they shape Russia’s risk calculus. A West that appears uncertain or divided encourages Moscow to believe that further escalation — whether in Odesa, Mykolaiv, or Moldova — may not trigger a decisive response. Mixed signals from Washington and European capitals have therefore become an enabling condition for Russia’s next phase of operations.

This analysis argues that Russia will continue consolidating its power in eastern and southern Ukraine and, in the spring, will move to fully landlock Ukraine, using Moldova as a low‑risk proving ground to gauge European resolve before considering more ambitious coercive actions against Finland and the Baltic States. Russia is not seeking peace; it is seeking time. Patience, attrition, and incremental advantage remain the core of its strategy, and the West risks misjudging the scale and immediacy of what is coming.

From Crimea to the Land Corridor

The origins of the present conflict lie in the aftermath of the 2014 Maidan Revolution, when Russia seized Crimea and sparked separatist uprisings in Donetsk and Luhansk. The annexation of Crimea was swift, decisive, and strategically transformative. By absorbing the peninsula, Russia secured the port of Sevastopol, gained uncontested control of the northern Black Sea, and established a permanent platform to pressure Ukraine.

In the Donbas, Russia pursued a different model: a grinding, low-intensity conflict designed to weaken Ukraine, drain its resources, and prevent its integration with Western institutions. The self-proclaimed “people’s republics” of Donetsk and Luhansk became frozen conflict zones — neither fully controlled by Russia nor fully governed by Ukraine. This ambiguity served Moscow’s interests for nearly a decade.

These events were not isolated crises but the opening moves in a long war. They established the pattern Russia continues to follow: seize key terrain, create political ambiguity, and treat time as a strategic asset. Yet they were only the prelude to the far more consequential struggle that began in 2022.

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022, it attempted a multi-axis assault to decapitate the Ukrainian government. The northern thrust toward Kyiv failed, but the southern and eastern offensives revealed Russia’s true priorities. After withdrawing from Kyiv and Kharkiv, Russia concentrated its forces on the Donbas and the southern coastline — the regions that matter most for long-term strategic control.

This recalibration was not a retreat from ambition. It was a recognition that the decisive terrain lay not in the capital but along the coastline, in the industrial east, and along the land corridor linking Russia to Crimea. By late 2022, Russia had entrenched itself across four major regions: Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson. These territories form the backbone of Russia’s current strategy and serve as staging grounds for what comes next.

Russia’s consolidation of Luhansk and Donetsk has given it control over much of the Donbas, a region rich in industrial infrastructure and Soviet-era logistics networks. These territories also carry ideological weight for Moscow, which portrays them as historically and culturally aligned with Russia. The slow, methodical capture of these regions has allowed Russia to build layered defenses, mobilize manpower, and create a fortified eastern front that Ukraine has struggled to penetrate.

Zaporizhzhia, by contrast, is the hinge of Russia’s southern strategy. Control of this region secures the land corridor from Russia to Crimea — a logistical lifeline that allows Russia to supply its forces without relying on the vulnerable Kerch Bridge. The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, the largest in Europe, also provides leverage: a strategic asset Russia can use to intimidate Ukraine and Europe.[3]

Kherson, the first major city Russia captured in 2022, remains strategically vital despite Ukraine’s liberation of the western bank of the Dnipro. Russia’s continued presence on the eastern bank protects Crimea’s northern approaches and allows Moscow to threaten Mykolaiv and Odesa. The Dnipro River has become a natural defensive barrier, enabling Russia to hold the region with fewer forces while maintaining strategic pressure.

Taken together, these four regions give Russia depth, defensibility, and the ability to project power westward and southward. They also serve as the staging ground for Russia’s next strategic objective, maritime dominance.

The Maritime Center of Gravity

Russia’s southern strategy centers on a series of key cities and ports that define the maritime geography of the conflict. The capture of Melitopol, Berdiansk, and Mariupol has already reshaped the strategic landscape. Melitopol serves as the logistical heart of the land bridge, a critical junction linking Russian forces in Donbas to Crimea. Berdiansk provides Russia with a secondary port on the Sea of Azov, enabling naval operations, logistics, and amphibious staging. Mariupol’s fall in 2022 was one of the war’s most consequential events, completing Russia’s control of the Sea of Azov and linking Russian-held territories into a continuous corridor.[4]

Yet these gains, significant as they are, represent only part of Russia’s maritime ambition. The true center of gravity lies further west, where Odesa and Mykolaiv form the last defensive shield preventing Russia from landlocking Ukraine. Odesa is Ukraine’s final major deep-water port — the gateway to global markets and the lifeline for grain exports that sustain both Ukraine’s economy and global food security. Mykolaiv, with its shipyards and industrial capacity, serves as the industrial bulwark protecting Odesa from the east.

Russia understands that without Odesa, Ukraine becomes a landlocked state dependent on overland routes through Europe. The maritime squeeze is therefore not merely a military objective but also an economic one. By controlling the Sea of Azov and restricting access to the Black Sea, Russia can strangle Ukraine’s economy, limit its export capacity, and increase its dependence on Western aid. The pressure on Odesa and Mykolaiv is thus part of a broader strategy to render Ukraine economically unsustainable.

This maritime strategy extends beyond Ukraine’s borders. Moldova, west of Odesa, has become a critical pressure point in Russia’s broader plan. If Russia can destabilize Moldova and pressure Odesa from the west, it can complete the maritime encirclement of Ukraine. A fully landlocked Ukraine would be economically strangled, dependent on Western aid, and unable to export grain and industrial goods at scale. This would give Russia enormous leverage in future negotiations and fundamentally alter the regional balance of power.

Moldova: The Proving Ground

Moldova has emerged as a critical pressure point in Russia’s broader strategy, as its recent elections strengthened pro‑Western forces in Chişinău and accelerated the country’s shift toward Europe. Now a formal candidate for European Union membership — with accession negotiations opened in late 2023 and formal talks that began in 2024 and continue to this day, Moldova is moving rapidly toward deeper political and economic integration with the West, a trajectory Moscow views as a direct challenge to its influence in a region it has long considered within its sphere.[5] Moldova is also a long‑standing member of the United Nations, fully recognized since 1992, which grants it international legitimacy and complicates any overt Russian intervention.[6]

Yet Moldova’s most consequential characteristic is its constitutional neutrality, which prevents it from joining NATO even as it cooperates closely with the alliance through the Partnership for Peace and various defense‑capacity programs.[7] This creates a uniquely vulnerable position: Moldova is aligned with the West politically and economically but not protected by NATO’s Article V guarantees. For Russia, this combination makes Moldova an ideal testing ground — a place where it can probe Western resolve, exploit political fragility, and assess whether Europe and the United States are willing to defend a non‑NATO partner before considering more ambitious moves against the Baltic States.

Transnistria — a narrow strip of land along Moldova’s eastern border — has been under the control of pro-Russian separatists since the early 1990s. Russian troops remain stationed there under the guise of “peacekeepers.”[8] Militarily, absorbing or fully controlling Transnistria would require little effort on Russia’s part. The region is isolated, lightly defended, and politically aligned with Moscow.

But Russia does not need Moldova for its resources or geography. It needs Moldova for what it represents: a test. A move against Moldova would allow Russia to determine whether Europe will respond collectively or fracture along political lines, whether NATO will treat aggression near its borders as a threat to the alliance, and whether Finland and the Baltic States would stand alone or with unified Western backing. Moldova is the perfect proving ground because the military risk is low, but the political signal is enormous. If Europe hesitates, Russia will interpret that hesitation as a green light for more aggressive coercion elsewhere. Whether Russia has the capacity to pursue that path is questionable.

Russia’s strategy is not built on rapid breakthroughs but on cumulative advantage. Moscow understands that Western political cycles create windows of opportunity. As the current U.S. administration continues to send mixed signals, Russia sees an opportunity to exploit uncertainty, fatigue, and shifting priorities.

Russia continues to rely on massed artillery, mobilized manpower, and fortified defensive lines. This approach is slow but effective. It forces Ukraine to expend resources faster than they can be replaced and strains Western stockpiles. Russia’s engagement with peace proposals is performative. Moscow uses ceasefire discussions to buy time, reposition forces, and shape international narratives. There is no evidence that Russia intends to negotiate a settlement that leaves Ukraine sovereign and intact.

By spring, Russia will likely consolidate its current lines in the east and south, intensify pressure on Odesa and Mykolaiv, conduct hybrid destabilization operations in Moldova, and use Transnistria as a pretext for intervention. These moves will test Europe’s willingness to respond and lay the political and military groundwork for future coercion against Finland and the Baltic States. Russia does not need to conquer these countries outright. It only needs to demonstrate that NATO will not defend them. Moldova is the rehearsal for that test.

The Test Ahead for Europe

Russia’s war in Ukraine is not a series of disconnected events but a coherent, long‑term strategy to reshape Eastern Europe’s security architecture. Each phase of the conflict — from Crimea to the Donbas to the southern land corridor — has advanced Moscow’s goal of weakening Ukraine, fracturing Europe, and reasserting Russian influence over the territories that once formed the Soviet Union’s strategic perimeter. The decisive terrain in this struggle is the south: the Black Sea, the ports, and the economic arteries that keep Ukraine alive. The decisive test, however, lies to the southwest. Moldova serves as a low‑risk proving ground where Russia can probe European and American resolve before considering more ambitious coercive actions.

If Russia succeeds in landlocking Ukraine and destabilizing Moldova, the balance of power in Eastern Europe will shift dramatically. A Ukraine cut off from the Black Sea would be economically strangled, dependent on Western aid, and unable to sustain long-term resistance. A Moldova thrown into crisis would expose the fragility of Europe’s political cohesion and cast doubt on the credibility of Western security guarantees. Such an outcome would not merely consolidate Russia’s gains in Ukraine; it would embolden Moscow to test the limits of Western tolerance elsewhere.

In such a scenario, the next targets are not hypothetical. The Baltic States — Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania — remain the most vulnerable frontline democracies in Europe. They are small, geographically exposed, and home to Russian‑speaking minorities that Moscow has repeatedly invoked in its narratives of “protection” and “historical unity.” An attack on the Baltics would align closely with Vladimir Putin’s long‑standing vision of restoring the influence, if not the borders, of the former Soviet Union. Finland, though now a NATO member with a formidable military, presents a more difficult challenge. By contrast, the Baltics offer Russia the symbolic and strategic opportunity to test Article V directly, forcing the West to show whether collective defense is a binding commitment or a political aspiration.

This is why Moldova matters so profoundly. Any Russian action there — whether hybrid destabilization, political manipulation, or overt military pressure — would serve as a rehearsal for a larger confrontation. It would allow Moscow to gauge whether the United States and Europe are prepared to respond decisively or whether political fatigue, internal division, and strategic hesitation will again create space for Russian escalation. The coming spring will not be a pause in the conflict. It will be the next phase of a long war — one in which Russia continues to tighten the vise, consolidate its gains, and test the foundations of European collective defense. The choices the West makes now will determine not only Ukraine’s future but also Europe’s security architecture for decades to come.

Dr. James M. Deitch was born in Philadelphia and raised in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. During his Marine Corps career, he deployed to Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq, Norway, and aboard the USS Saratoga. Deitch holds a master’s degree in military history from Norwich University and a doctoral degree in intellectual history from Liberty University. His published works can be found in USNI’s Proceedings, Total War Magazine, Concealed Carry Magazine, Real Clear Defense, and the Journal of the American Revolution.

[1] Barak Ravid and Dave Lawler, “Trump’s Ukraine‑Russia Peace Plan, in the Full 28 Points,” Axios, November 20, 2025. “Exclusive: Trump’s Full 28‑Point Ukraine‑Russia Peace Plan,” MSN, December 2025. “Trump’s Ukraine‑Russia Peace Plan, in the Full 28 Points,” The New Arab, November 2025.

[2] Michael Kofman and Rob Lee, “The Russian Military’s Lessons From Ukraine,” Foreign Affairs 102, no. 6 (November/December 2023). Liana Fix and Michael Kimmage, “What If Ukraine Loses?” Foreign Affairs 102, no. 5 (September/October 2023).

[3] International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), “IAEA Director General’s Update on the Situation in Ukraine,” IAEA.org, March 2023.

[4] Andrew E. Kramer, “Russia Claims Full Control of Mariupol, Securing the Sea of Azov,” The New York Times, May 20, 2022.

[5] European Commission, “EU–Moldova Relations,” European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations, last modified September 22, 2025.

[6] United Nations, “Member States: Republic of Moldova,” UN.org, accessed December 21, 2025

[7] North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Relations with the Republic of Moldova,” NATO.int, last updated July 2025.

[8] Organization for Security and Co‑operation in Europe (OSCE), “Mission to Moldova: Background and Mandate,” OSCE.org, accessed December 21, 2025.